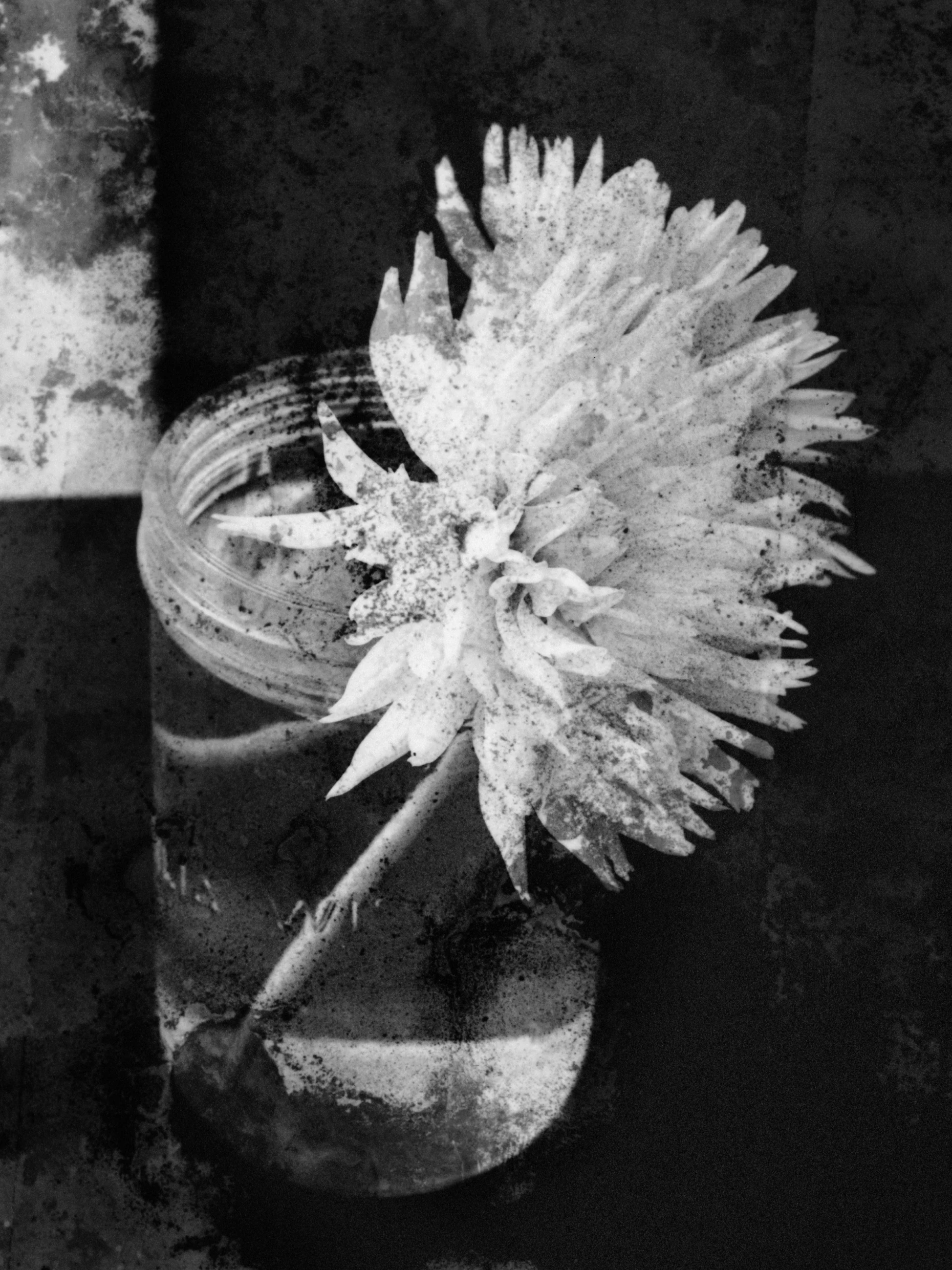

You could be forgiven for thinking that her photographs had always been there, that they had been freshly rediscovered in an old trunk, taken from a notebook lost on a riverbank a century ago. Images of a child’s face, a dark forest, shadows streaked across the paper, a few still-life photos of timeless grace. Born in Minsk, Belarus, Alexandra Catiere cultivates a keen understanding of optics and the organic, but also harvests everything that usually escapes the eye – “the Breath of Being”, “The Vital Impulse of Solidarity”, to reference the title of her most recent work. Something invisible and tenuous that illuminates a face, connects one being to another, or breathes life into the still-life.

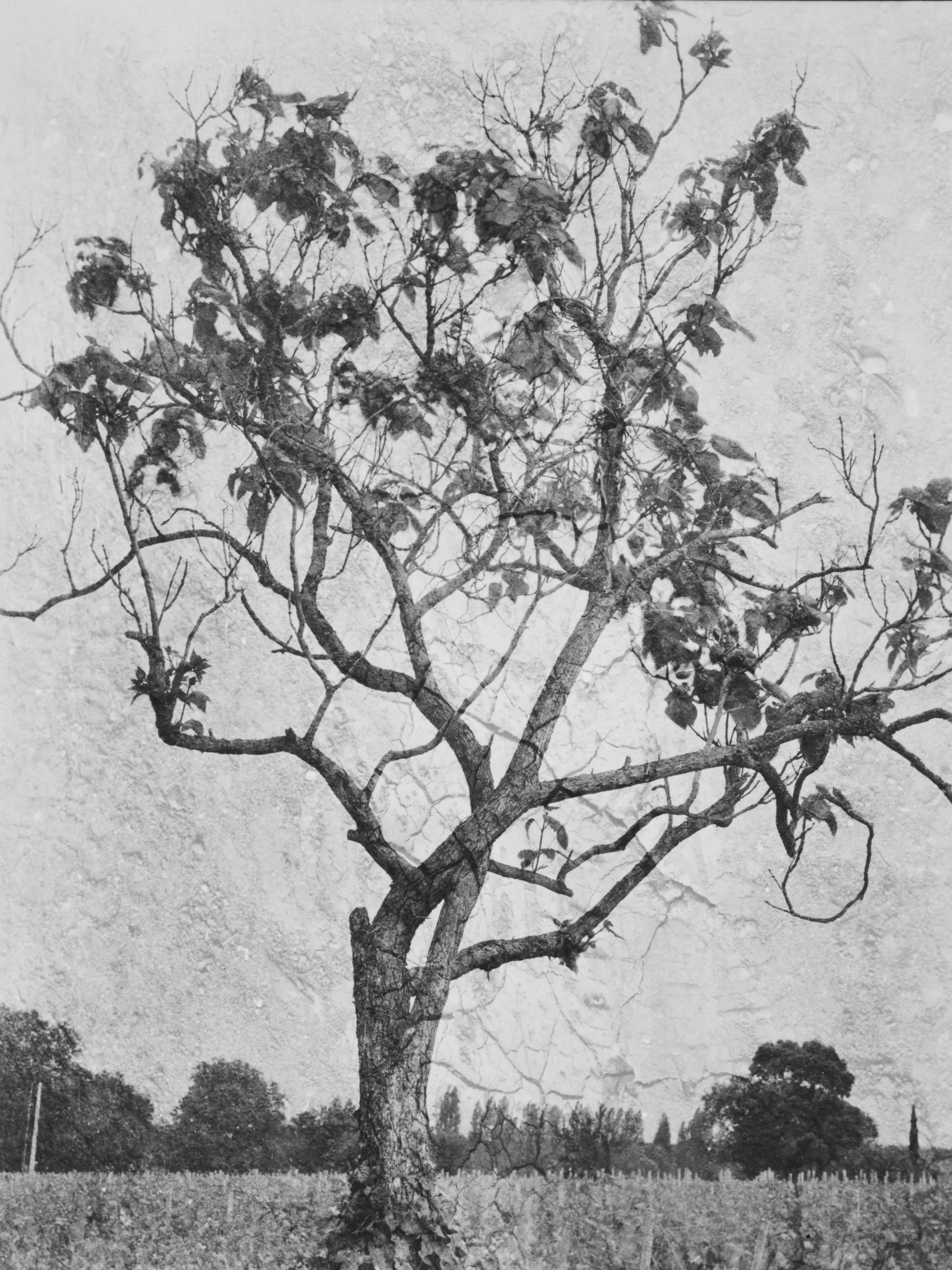

Awarded the 2024 Camera Clara Photo Award and exhibited at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris in 2025, the artist also set up her view camera in the middle of the Château Palmer vineyards for the fourth edition of the INSTANTS residency, where she followed the passage of time by superimposing layered images like layers of paint, capturing the vast and beautiful self-evidence of nature that survives the generations of men and women who have passed through it.

CHÂTEAU PALMER : You have often photographed vegetation, cherry blossoms, grasses, leaves and more. You work with the organic and the mineral, right up to printing. As you wandered through the vineyards, you said you were struck by the peaceful joy of the place. What do you mean by that?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : I remembered tasting a grand cru and the effect it had on me; an overflowing of dopamine, a deep joy inevitably reflecting truth and authenticity. The truth of a terroir, of the men and women who have created a wine capable of producing such intense emotion, who have received a vision of nature and an expertise from their elders, which they will then pass on to future generations. Joy was therefore one of the key words when I arrived at Château Palmer, and I quickly felt it in the atmosphere, in the philosophy of the estate, in the way they work the land by using herbal teas to protect the plants or by burying manure in horns to produce fertiliser. All of this touched me. I had read Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture Course and learned about biodynamics, and I see this as common sense, a return to natural practices that I have always known from where I grew up. The ways that were respected by the old Belarusian farmers, but also by my parents, in the garden of their dacha outside the city, where they grew fruit and vegetables. When I arrived in the United States at the age of 25, I discovered tomatoes that had no aroma and no flavour, and I realised that something was wrong. Whereas the tomatoes grown here in Palmer are like Proustian madeleines; they carry the taste of childhood.

“I am trying to recapture the excitement of the early photographers, that joy of interacting with light and matter”

— Alexandra Catiere

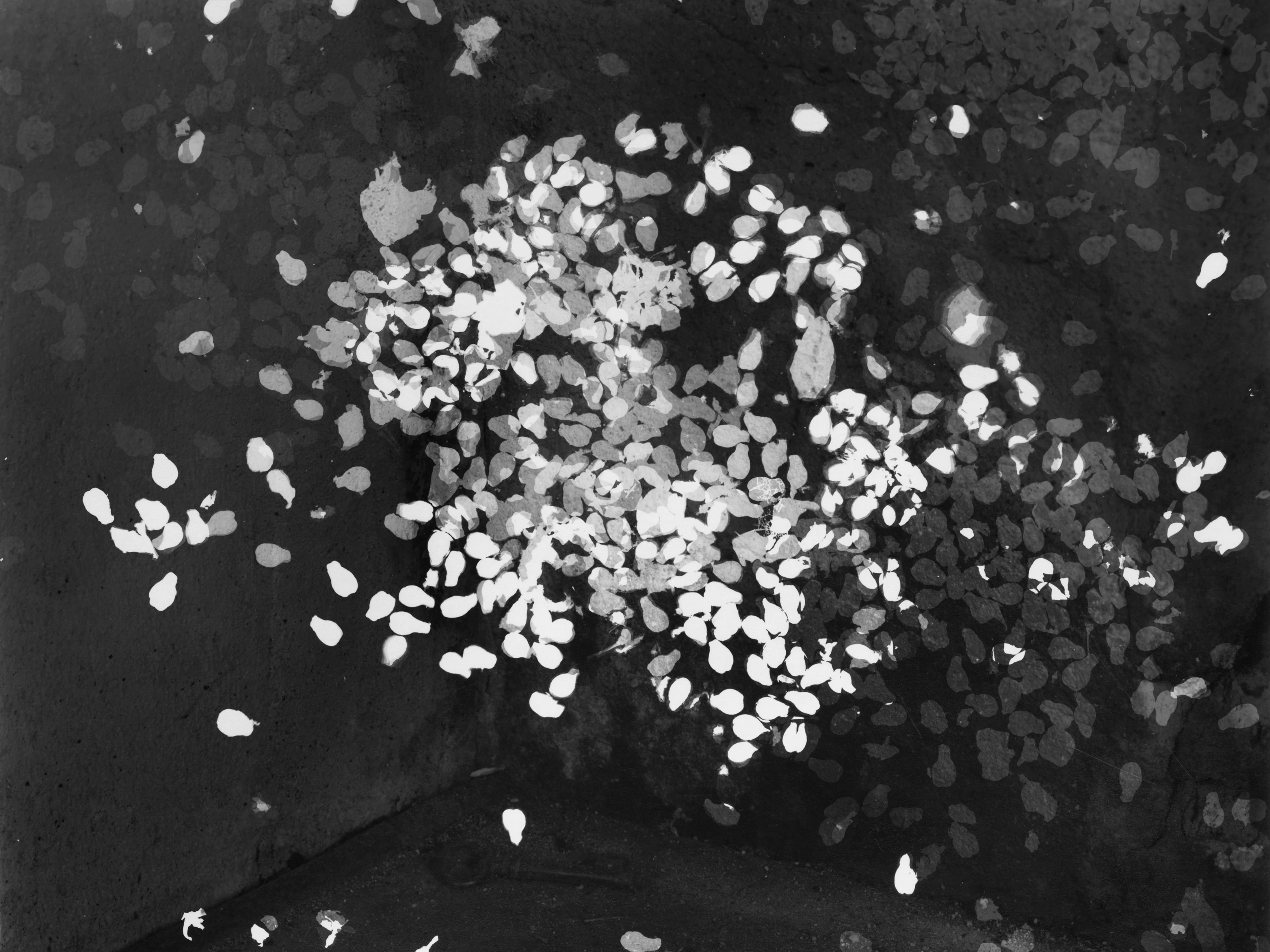

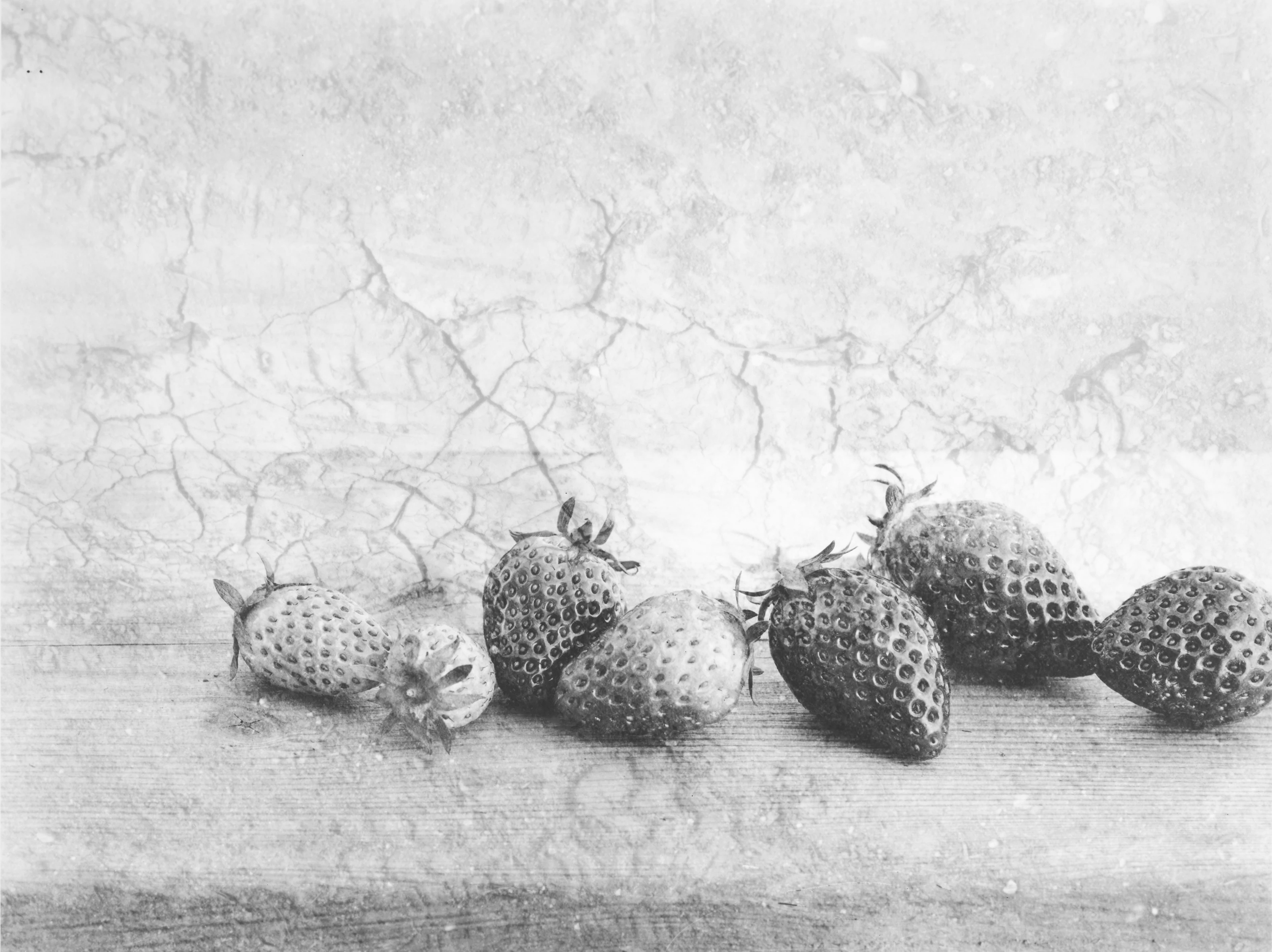

CHÂTEAU PALMER : You photographed these tomatoes, as well as other fruits and vegetables from the orchard, the daily catch from local fisheries, the château’s crockery and silverware, and then you began to superimpose the images to tell a story. What was your process?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : I definitely didn’t want to photograph the vines or the grapes. It seemed too literal, too obvious. I had to try something else. Focus my gaze on less expected elements, such as the role of trees in the vineyard, the produce from the orchard, and yes, even the silverware. I come from a culture where none of that existed. Antique objects have disappeared. Everything has been destroyed, erased. In the former Soviet Union, there is no past, no history. We don’t talk about it and we don’t see it. So for you, it may be normal to eat with forks or knives that are over a century old; for me, it is very novel.

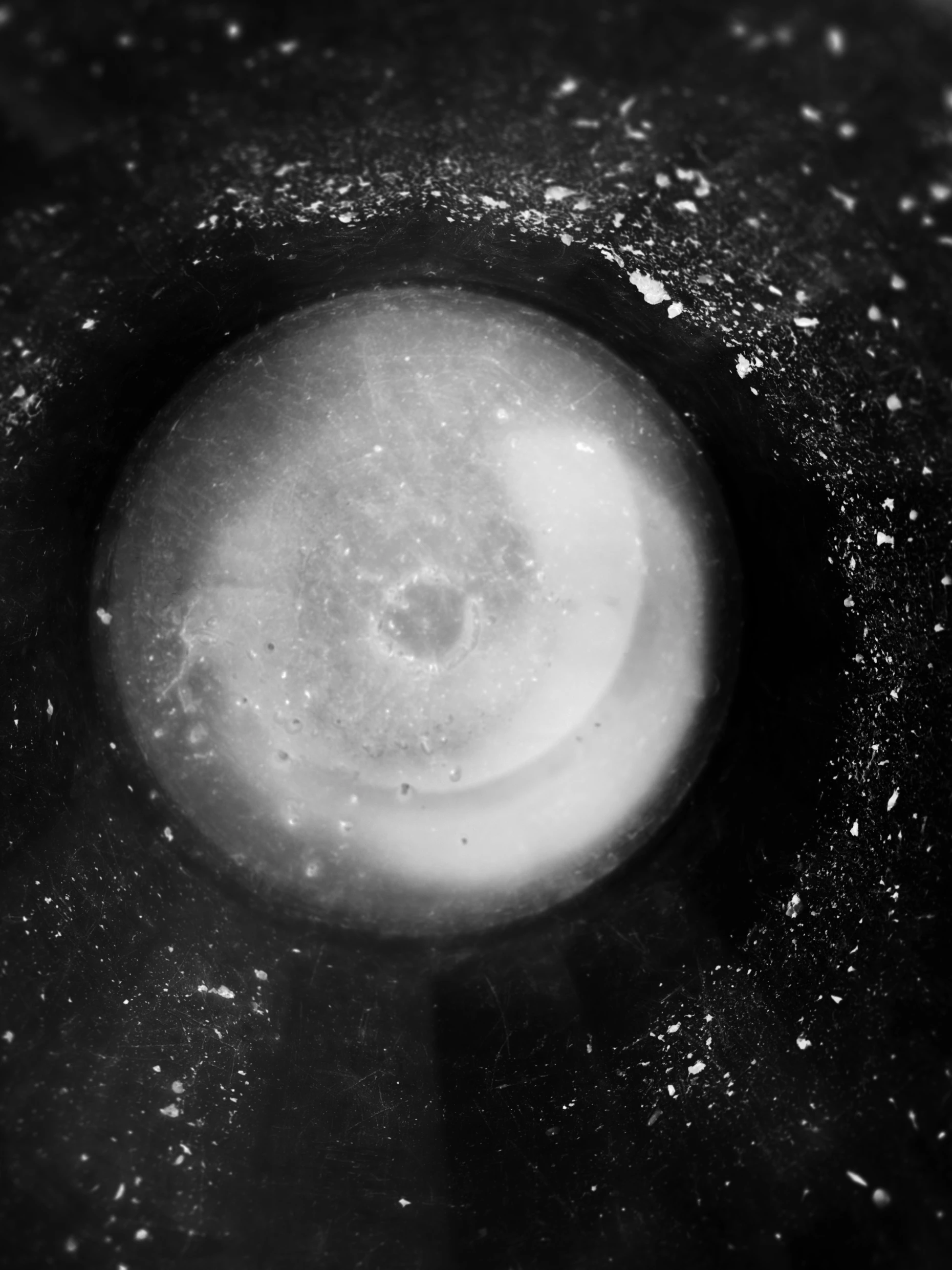

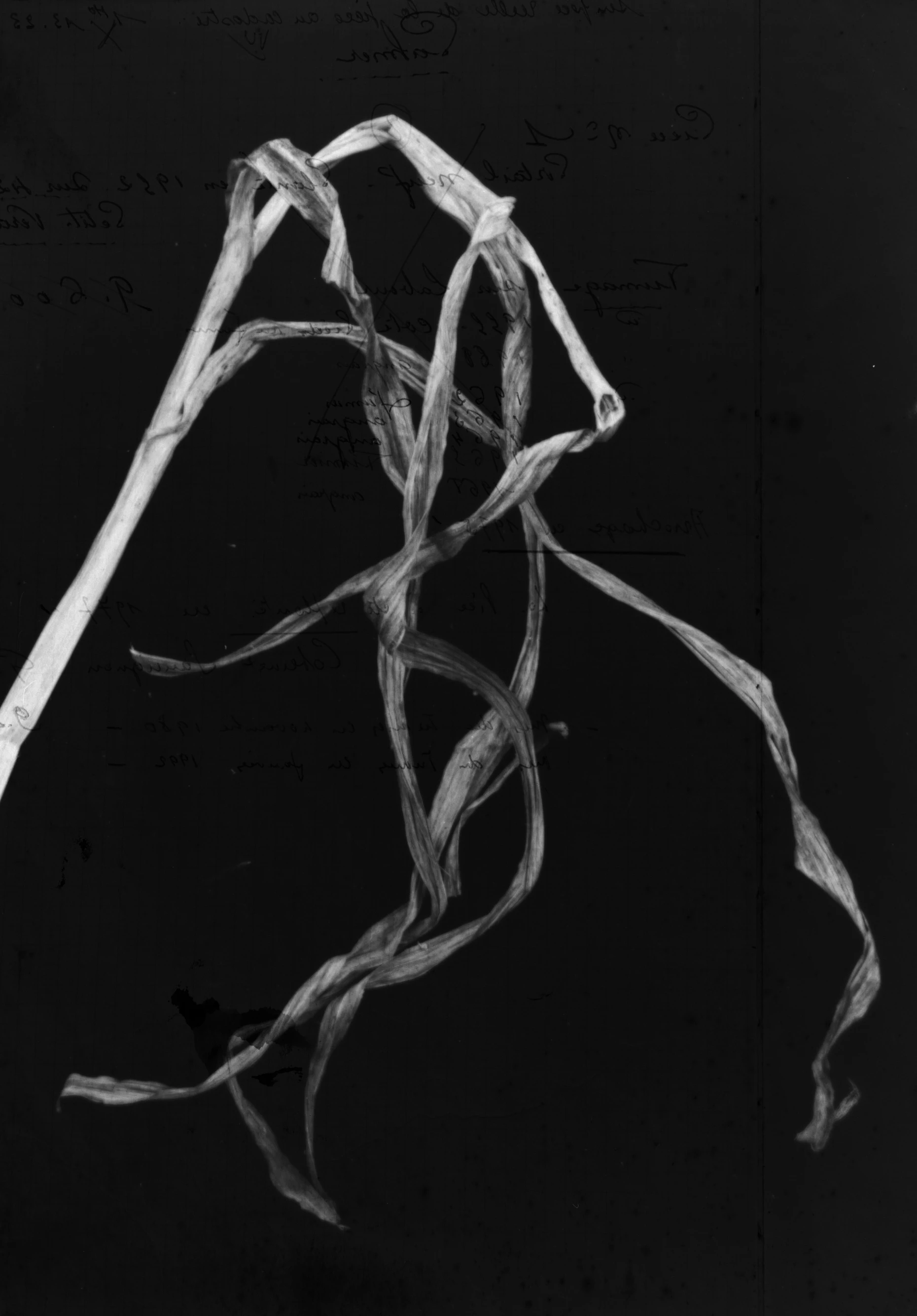

In a similar way, I was struck by some graffiti on one of the castle walls upstairs, evidence of the German occupation during the World War II. I was impressed that the owners had kept it. I come from a country where all that was taboo. In Minsk, just after the war, the government didn’t even want to see the wounded and disabled in the city. They had to maintain the country’s image, even if it meant sweeping everything under the carpet. That is why I have always been sensitive to what goes on behind closed doors. I like to open them and reveal the stories hidden inside. This gave me the idea of photographing the German graffiti on the wall and using it as a base, a palimpsest of sorts, a first layer of paint that I could cover with other images. I reproduced this process with the harvest notebooks kept by the former managers, the Chardon family, superimposing images of what continues to exist today onto the handwritten pages from the past.

That was the turning point of this residency – which to me was much more than a carte blanche: it allowed me to explore what has always obsessed me, this idea that history is not chronological but condensed within us. All the strata of the past–my Belarusian childhood, family secrets, artistic encounters–coexist simultaneously in my memory and resurface without warning when I encounter a place, a light. At Palmer, everything spoke to me: the German graffiti on the wall, the handwritten harvest notebooks, the century-old silverware. These material traces reminded me of the frescoes of Pompeii, which continue to speak to us across the centuries. Photographing this estate, I understood that I was not trying to freeze the present moment, but to reveal this thickness of time that makes a place breathe long after those who inhabited it have passed. This is where the title of this work was born: "Everything here will outlive me." The vines, the walls, the earth will carry within them the memory of this encounter, just as I carry within me all the stories that have passed through me.

CHÂTEAU PALMER : Are these superimpositions also a form of homage to the experiments of the pioneers of photography, to Man Ray’s photograms, for example?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : Let’s say that I am trying to recapture the excitement of the early photographers, that joy of play, of interacting with light and matter. That is where it all started. I don’t like photography that is too cerebral or too abstract. I could have decided to bury prints like cow horns, to try to completely reinvent myself, but that is not in my nature. I prefer to refine my own practice, to push it further and further while remaining true to myself. I want to preserve the beginner’s spirit at all costs, that mixture of anxiety and excitement. For me, ideas come first from the material, from work. Sometimes from accidents, from fruitful mistakes. That is why I love working with film so much. The creative process takes place largely after the shot is taken, during development and printing. I test different papers in the darkroom, I can add earth to the negatives, compare inks and textures, and bring the images to life in different ways. That is when I really create. I think about the status of the imprint, of the trace. What kind of trace will we leave behind? What survives accidents, fashions, lifecycles, decades, centuries? These questions are at the heart of my approach and are the opposite of what things like artificial intelligence could produce. AI would merely copy, plagiarise and quote, without ever achieving the magic I seek, which comes from the depth of the material and the joy of truth.

“I understood that I was not trying to freeze the present moment, but to reveal this thickness of time”

— Alexandra Catiere

CHÂTEAU PALMER : Looking at your images, a few leading names from humanist black-and-white photography spring to mind, from André Kertész to Claude Batho. But also figures from a certain pictorial tradition such as Chardin, the Barbizon School, the Impressionists, and Cézanne. Would you agree?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : I took up photography to leave my country. There were several possible fields of study in the United States including journalism, cinema and politics. I was unsure until one day, in the library in Minsk, I came across a book called History of Photography. It was the only book devoted to the discipline. In it, I discovered the work of Alfred Stieglitz and other pioneers of 19th-century photography. It was a shock, a revelation. I had turned my back on painting at the age of 15, even though I loved it. I had reached an impasse. Through photography, I realised that I could return to my artistic practice and explore the painting I had abandoned, but from another angle. I bought an old camera, learned printing techniques in a friend’s bathroom, and then left for the United States.

CHÂTEAU PALMER : Where you quickly became the assistant to the famous Irving Penn… How did that encounter come about?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : When I arrived in New York City, I knew nothing about the world of photography. I got a scholarship to train at the International Center of Photography (ICP), where I worked day and night. It was a whole new world, full of books, libraries and museums. To get contracts or internships, a friend advised me to call photographers directly. I really liked Richard Avedon, who had impressed me at a conference, but he had just died. So I found the phone number of Mr. Penn’s studio. Somebody answered and said, “Send us a fax.”

A few months later, his assistant called me back for a trial. The first time I met with Mr. Penn, I was almost disappointed. He was short, he looked old, and he vaguely resembled my grandfather. He asked me about my ambitions and I answered with a certain arrogance. When I left the interview, I felt so useless that I cried for two days. Then he recontacted me. It was like a miracle. I spent a year in his studio on Fifth Avenue, where I managed the prints and archives and helped with some of the shoots. It was an intense learning period and a crucial one for me. I am grateful to him for that. When my visa expired and I returned to Minsk, I started photographing people on the bus, their heads pressed against the window. My approach was not voyeuristic but very personal. This series, Behind the Glass (2005), became my calling card, earning me a publication in The New Yorker and an invitation to a major photography festival. Suddenly, my career took off.

CHÂTEAU PALMER : Before continuing in France…

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : In 2008, I moved to Paris with my husband, photographer Raphaël Dallaporta. At first, people in France constantly reminded me of my Belarusian origins and my accent, as if my time in the United States had meant nothing. Despite this, I continued to work in fashion and for the press, taking portraits in the studio. Then, within the space of a year, I lost my brother to cancer and I had a son. These personal ordeals, with death and birth confronting each other, had a significant impact on my work, giving me the freedom to create things that were more chaotic and ultimately closer to life. I began to mix series, subjects and territories, breaking down chronology and boundaries. Thanks to this new direction, I was awarded a residency at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône, and my work was exhibited at Les Rencontres Photographiques d’Arles and Paris Photo. And here I am today, in the midst of the grape harvest at Château Palmer!

“I love the silence of the darkroom; it is very monastic, very meditative”

— Alexandra Catiere

CHÂTEAU PALMER : How do you find inspiration on a daily basis?

ALEXANDRA CATIERE : I love the silence of the darkroom; it is very monastic, very meditative. Before I start work, I sometimes read Russian poetry aloud. Texts by Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) or Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) that resonate with my images. There is something in Russian culture that goes to the heart of the matter, seeks the soul of things and beings, and strives to express the invisible. I like this idealism; it speaks to me, this spiritual dimension, this purity. Sometimes, in the fashion world, people seem surprised to see me working on black and white portraits, using a view camera just like in the old days. Yet it is completely natural for me. These are tried and tested methods, just as it seems natural to you at Château Palmer to eat vegetables from the garden or have lunch together in the winegrowers’ canteen, regardless of your age or your position in the company.

The technological leap we have experienced in recent years should not make us forget the original beauty of our practice. The need to reach out to people, to be present in the moment. When I paint portraits, I seek to capture the spark of life, the sacred fire, the duende as they say in flamenco. I also think of the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, who cultivated this majestic form of simplicity, of obviousness. The artist lived with his sisters in a small village near Bologna. When his brushes were no longer usable, he did not throw them away; he buried them. The magic of his still-life works comes from there, from the love that still breathes today on the canvas. I hope to convey the same sincerity and sensitivity through my photography.

Photographs © Alexandra Catiere for the INSTANTS residency at Château Palmer, 2025

BIOGRAPHY

Alexandra Catiere’s life path, from the former Soviet Union to the United States and then to France, both scorns borders and testifies to her striving for universality. The photographer has made timelessness a salient feature of an oeuvre that revives photography’s humanistic tradition in a virtuoso capturing of sensation and atmosphere. Never settling simply for portrait or reportage, Alexandra uses the camera to express her empathy with human nature and, most of all, with life itself.